Taiwan's Regions Explained

When most travellers think of Taiwan, they picture Taipei’s glittering night markets and perhaps the towering presence of Taipei 101. But Taiwan is far more than its capital city. This small island—roughly the size of Belgium or slightly smaller than Switzerland—contains extraordinary geographic and cultural diversity that rivals nations many times its size.

Understanding Taiwan’s regional divisions isn’t just about knowing which city sits where on a map. It’s about recognising that this compact island encompasses tropical beaches, alpine forests reaching nearly 4,000 metres, volcanic archipelagos, indigenous cultures that predate Chinese settlement by thousands of years, and regional identities shaped by distinct historical experiences. The regional differences you’ll encounter aren’t merely cosmetic; they reflect genuine variations in climate, cuisine, language, pace of life, and even political attitudes.

This guide will help you understand Taiwan’s six main regions so you can make informed decisions about where to spend your time based on your interests, the season you’re travelling, and the kind of experience you’re seeking.

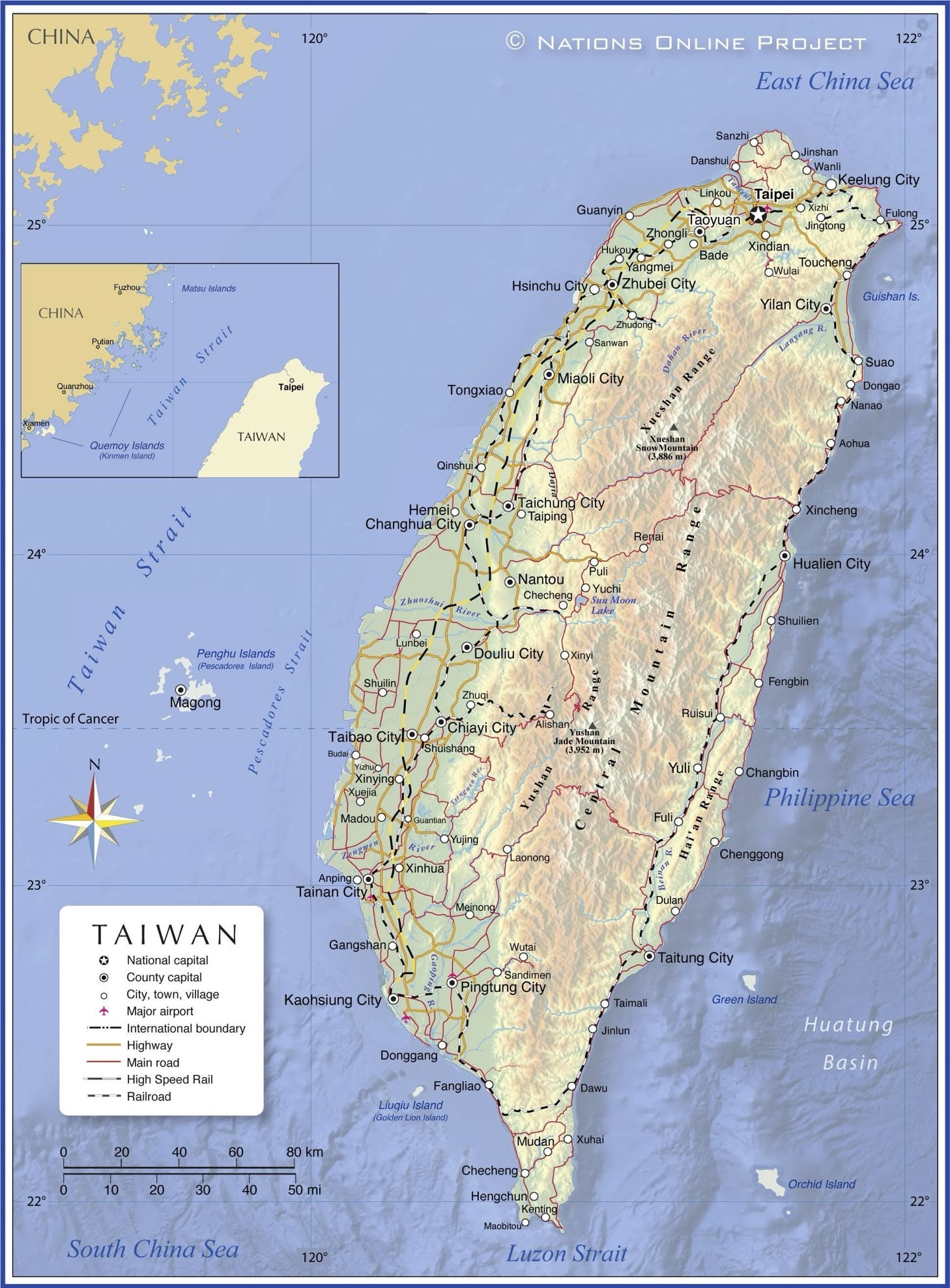

Visualising Taiwan’s Geography

Before diving into the regions, it helps to understand Taiwan’s basic geographic layout. The island stretches approximately 394 kilometres from north to south and about 144 kilometres at its widest point from east to west. A dramatic mountain range, the Central Mountain Range, runs like a spine down the island’s eastern side, creating a natural barrier that has profoundly shaped Taiwan’s development.

This mountain backbone means that most of Taiwan’s population, infrastructure, and economic activity concentrate along the western coastal plains, whilst the eastern side remains comparatively rural and less developed. The mountains themselves aren’t just a backdrop; they form their own distinct region, with peaks reaching above 3,000 metres and ecosystems that shift from subtropical to temperate within a short vertical distance.

Surrounding the main island are several offshore island groups, each with unique geological origins and cultural characters. Understanding this basic geography - western plains, eastern coast, central mountains, and scattered islands - provides the framework for everything else you’ll learn about Taiwan’s regions.

The Six Main Regions

Taiwan is commonly divided into six main regions: North, Central, South, East, Offshore Islands, and High Mountain1. Unlike the rigid administrative divisions you might find on official maps, these regional groupings reflect how Taiwanese people actually think about and experience their island’s geography.

Northern Taiwan

What It Encompasses

Northern Taiwan includes Taipei City, New Taipei City, Keelung, Taoyuan, Hsinchu, and Yilan County. This is Taiwan’s political, economic, and cultural centre of gravity.

Distinctive Characteristics

The north represents Taiwan’s most cosmopolitan face. Taipei, as the capital, has absorbed waves of migrants from across China, creating a diverse urban culture that’s more transient and less rooted in local tradition than other parts of Taiwan. The presence of government institutions, international corporations, and prestigious universities gives the north a distinctly metropolitan character.

However, northern Taiwan isn’t just about Taipei’s urban sprawl. The region encompasses dramatic coastlines at Keelung and the Northeast Coast, the volcanic landscapes of Yangmingshan, hot spring towns like Beitou and Wulai, and the historic gold-mining settlement of Jiufen. Hsinchu serves as Taiwan’s Silicon Valley, whilst Yilan to the east offers a glimpse of more relaxed, nature-focused living that feels worlds away from Taipei despite being less than an hour by train or bus.

Key Highlights

The north offers the fullest range of international amenities, the most developed public transport system, and the easiest access to English-language resources. It’s where you’ll find the densest concentration of museums, contemporary art spaces, and international dining options. The region also serves as the gateway to Taiwan, with Taoyuan International Airport located here.

For nature seekers, the north provides surprisingly accessible escapes. You can hike volcanic peaks overlooking the city, soak in hot springs, or explore the dramatic coastline where the mountains meet the sea—all within easy reach of Taipei’s metro system.

Who Should Prioritise This Region

First-time visitors with limited time often focus on the north because it offers a comprehensive introduction to Taiwan with the lowest language barriers. It’s ideal for travellers who want urban sophistication alongside accessible nature, those conducting business, and anyone who wants the reassurance of well-developed tourist infrastructure.

However, if you want to escape tourist crowds or experience slow living pace, the north’s urban areas may disappoint. The region’s rapid modernisation means that it is always hectic.

Climate Considerations

Northern Taiwan experiences a subtropical climate with humidity due to monsoon. Winters (December to February) are mild but frequently grey, drizzly, and surprisingly damp—expect temperatures of 12-20°C, but the humidity and persistent rain make it feel colder than the thermometer suggests. The northeast monsoon brings extended periods of rain, particularly from November through March.

Summers are hot and humid (often exceeding 35°C with high humidity), with intense afternoon thunderstorms common from June through August. The typhoon season peaks from July to September. Spring (March to May) and autumn (October to November) offer the most pleasant weather, though spring can still be quite rainy.

Central Taiwan

What It Encompasses

Central Taiwan includes Taichung City, Changhua County, Nantou County, and Yunlin County, and Miaoli County. This region serves as Taiwan’s geographic heart and represents a transitional zone between north and south in multiple respects.

Distinctive Characteristics

Taichung, Taiwan’s second-largest city, embodies a different urban character from Taipei—more spacious, car-oriented, and residential, with a reputation for pleasant weather and a relaxed lifestyle. The city has invested heavily in cultural infrastructure in recent years, with impressive museums and performance venues that rival those in the capital.

Moving inland from Taichung, you encounter Nantou County, Taiwan’s only landlocked county, which contains some of the island’s most celebrated natural attractions. This is where the mountains truly begin to dominate the landscape. Sun Moon Lake, Taiwan’s largest body of water, sits here surrounded by forested peaks and indigenous Thao villages. The high-altitude resort areas of Cingjing Farm offer alpine scenery that feels transported from Switzerland.

Changhua and Yunlin County to the west represents traditional agricultural Taiwan, with its flat plains historically devoted to rice cultivation. This area sees fewer international tourists but offers insights into Taiwan’s rural life and traditional industries.

As for Miaoli County, it is one of the manufacturing centres in Taiwan, and famous for its Hakka culture.

Key Highlights

Central Taiwan excels at providing accessible mountain experiences without requiring serious trekking. Sun Moon Lake offers gentle trails, cycling paths, and cultural sites around its shores, whilst higher-altitude areas like Hehuanshan provide alpine scenery accessible by road. The region also contains important temples like Taichung’s Zhenlan Temple, one of Taiwan’s most significant sites for Mazu worship.

For food enthusiasts, central Taiwan offers distinct culinary traditions. Taichung claims several iconic foods, including sun cakes, bubble tea (which originated here), and a particular style of noodles. The region also produces much of Taiwan’s tea, with plantations scattered across the mountainous areas of Nantou.

Who Should Prioritise This Region

Central Taiwan suits travellers seeking a balance between urban amenities and mountain access. It’s excellent for those interested in Taiwan’s indigenous cultures (the Thao around Sun Moon Lake, the Tsou in Alishan), tea culture, and accessible alpine scenery. Photographers particularly appreciate the region’s misty mountain landscapes.

The region works well for travellers with moderate mobility who want mountain experiences without extreme hiking, and for those seeking to understand Taiwan beyond the Taipei bubble without venturing too far from urban infrastructure.

Climate Considerations

Central Taiwan enjoys more favourable weather than the north, with less rain and more sunshine throughout the year. Taichung is often described as having Taiwan’s best climate—warm and relatively dry, with milder winters than the north (typically 14-24°C) and hot but manageable summers.

However, climate varies dramatically with altitude. Sun Moon Lake sits at about 760 metres and experiences cooler temperatures with frequent mist, whilst high-altitude areas like Hehuanshan (above 3,000 metres) can see frost and occasionally snow in winter. The mountains also create their own weather patterns, with afternoon mist and rain common at higher elevations even when the plains are clear.

Southern Taiwan

What It Encompasses

Southern Taiwan includes Tainan City, Kaohsiung City, Pingtung County, and Chiayi County. This region represents the heart of traditional Taiwanese culture and the cradle of Han Chinese settlement on the island.

Distinctive Characteristics

The south has a fundamentally different character from the north. Tainan, Taiwan’s oldest city, served as the island’s capital for over 200 years and remains its spiritual and cultural heart. The city’s pace is noticeably slower, its streets lined with centuries-old temples, traditional markets, and family businesses that have operated for generations. This is where you’ll find Taiwan’s deepest culinary traditions and strongest sense of local identity.

Kaohsiung, Taiwan’s third-largest city and primary international port, presents an industrial powerhouse that’s undergone remarkable transformation. Once known primarily for heavy industry and pollution, Kaohsiung has reinvented itself with waterfront developments, public art projects, and a generally more liveable urban environment. It maintains a grittier, more working-class character than Taipei, with a distinct local pride.

Pingtung County, stretching south to Taiwan’s tropical tip, offers beach towns, the surfing haven of Kenting, and indigenous Paiwan and Rukai villages in its mountainous interior. The landscape becomes notably more tropical here, with coconut palms and other vegetation that signal you’ve crossed into a different climate zone.

Chiayi County is like Changhua and Yunlin County, also featuring traditional agriculture because of its flat plains. Besides, it’s also famous for Alishan National Forest Recreation Area, making it one of the must-go county in the south.

Key Highlights

The south is unmatched for food culture and religious heritage. Tainan alone contains hundreds of temples, each with its own history and festivals. The city’s snack culture is legendary: small, inexpensive dishes served from generation-old street vendors and tiny restaurants. Understanding southern food culture provides perhaps the deepest insight into traditional Taiwanese life available to outsiders.

Kaohsiung offers urban experiences distinct from Taipei, particularly its harbour culture and the vibrant Zuoying district with its Lotus Pond temples. Kenting National Park at Taiwan’s southern tip provides tropical beach experiences, though it has become heavily developed and can feel overcrowded during peak seasons.

The south also provides access to Alishan, one of Taiwan’s most famous mountain areas, renowned for its sunrise views, historic logging railway, and tea plantations.

Who Should Prioritise This Region

Southern Taiwan rewards travellers interested in history, traditional culture, and authentic food experiences. It’s ideal for those who want to see Taiwan beyond the modernised, internationalised north, and who are comfortable navigating places with fewer English speakers.

Foodies should absolutely prioritise the south, particularly Tainan. The region also suits those interested in Taiwan’s complex religious landscape, traditional Han cultures, and anyone wanting to experience how the vast majority of Taiwanese people actually live outside the capital.

Beach seekers may be drawn to Kenting, where travellers can participate in various water activities and see coral reefs.

Climate Considerations

Southern Taiwan is noticeably warmer than the north throughout the year. Winters are mild and pleasant (typically 17-26°C), though the coldest fronts can still bring temperatures down to around 10°C for brief periods. This makes the south an excellent winter destination when northern Taiwan is grey and drizzly.

Summers are intensely hot and humid, with temperatures regularly exceeding 35°C and feeling even hotter due to high humidity. The region receives less rain than the north overall, with most precipitation coming in brief, intense afternoon thunderstorms during summer. Typhoons affect the south less frequently than the north and east, though when they do hit, they can be severe.

Kaohsiung City and Pingtung County are genuinely tropical, with warm weather year-round and a distinct dry season from November through March—the best time for beach activities.

Eastern Taiwan

What It Encompasses

Eastern Taiwan includes Hualien County and Taitung County, separated from the western side of Taiwan by the Central Mountain Range. This region comprises nearly half of Taiwan’s land area but contains less than 10 per cent of its population.

Distinctive Characteristics

Eastern Taiwan feels like a different island entirely. The dramatic mountains rise almost directly from the Pacific coast, leaving only narrow coastal plains. Development is constrained by geography, with just a few sizeable towns connected by a winding coastal road and rail line. The result is Taiwan’s most unspoiled and naturally spectacular region.

This is Taiwan’s indigenous heartland. While indigenous peoples represent only about 2 per cent of Taiwan’s total population, they comprise a much larger proportion in the east. Amis, Bunun, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, and other indigenous groups maintain stronger cultural continuity here than anywhere else on the island. Many villages still practice traditional festivals, languages, and customs.

The east’s relative isolation has preserved both natural and cultural elements that vanished elsewhere. Rice paddies run right to the edges of mountains, small fishing villages line the coast, and the pace of life remains unhurried. However, this same isolation means fewer amenities, less English signage, and more challenging logistics for independent travellers.

Key Highlights

Taroko Gorge stands as eastern Taiwan’s marquee attraction: a marble canyon with sheer walls rising hundreds of metres, carved by the Liwu River over millions of years. The gorge offers hiking trails ranging from easy walks to challenging climbs, all amid genuinely spectacular scenery.

Beyond Taroko, the east offers the East Rift Valley, a fertile agricultural region running between two mountain ranges; the coastal road from Hualien to Taitung, with dramatic sea cliffs and hidden beaches; and numerous hot springs, both developed and wild. Taitung offers a more relaxed pace, aboriginal cultural experiences, and access to Green Island and Orchid Island (in this post we classify them into the offshore islands region).

The east is Taiwan’s premier destination for outdoor activities: hiking, river tracing, diving, surfing, paragliding, and simply appreciating dramatic natural landscapes less modified by human activity.

Key Considerations

Eastern Taiwan rewards travellers who prioritise natural beauty and outdoor experiences over urban amenities. It’s ideal for those comfortable with less developed infrastructure, fewer English speakers, and more limited food options (particularly for vegetarians and those with dietary restrictions).

The east suits travellers who want to slow down, spend time in nature, and gain insight into Taiwan’s indigenous cultures. It’s also excellent for those seeking to escape the tourist crowds that concentrate in the west, though Taroko Gorge itself can be very busy.

However, the east requires more planning. Public transportation is limited compared to western Taiwan, so having a car or scooter provides much more flexibility. Accommodation and dining options are more spread out and can be limited in smaller towns.

Climate Considerations

Eastern Taiwan’s climate is heavily influenced by the Pacific Ocean and the mountains. Summers are hot and humid, though coastal areas benefit from sea breezes. Winters are mild but can be surprisingly wet and grey, particularly around Hualien.

The region faces directly into Pacific weather systems, making it particularly vulnerable to typhoons from July through October. When typhoons approach, they almost always affect the east first and most severely. The northeast monsoon also brings persistent rain and wind from October through March, particularly affecting northern areas like Hualien.

The most reliable weather comes in spring (April to May) and autumn (October to November), though even these seasons aren’t guaranteed. For beach and outdoor activities, summer offers the warmest water and most stable weather between typhoons, whilst winter is better for hiking in the mountains when higher elevations become more comfortable.

Offshore Islands

What It Encompasses

Taiwan’s offshore islands include several distinct archipelagos: Penghu (the Pescadores), Kinmen, Matsu, Green Island, Orchid Island, and several smaller islands. Each has its own distinct character, history, and appeal.

Distinctive Characteristics

These islands are united more by what they’re not (part of the main island) than by any shared characteristics. Penghu sits in the Taiwan Strait, famous for its basalt columns, beaches, and seafood. Kinmen and Matsu, located just kilometres from mainland China, served as frontline military outposts during the decades of cross-strait tension and retain a unique militarised heritage.

Green Island and Orchid Island lie off Taiwan’s southeast coast. Green Island is known for underwater hot springs, diving, and snorkelling, whilst Orchid Island (Lanyu) is home to the Tao people, one of Taiwan’s indigenous groups with distinct cultural practices including their iconic traditional fishing boats. Also Orchid Island is more nature-preserved than Green Island.

These islands offer escapes from the main island’s density and commercialisation. Most have small populations, slower paces of life, and economies based on fishing, agriculture, and increasingly, tourism. However, “escape” often means limited amenities, restricted transportation, and vulnerability to weather that can strand travellers.

Key Highlights

Penghu excels as a summer beach destination, with clearer water and better beaches than most of the main island. The basalt formations at Daguoye and other sites offer unique geological attractions. The islands also host the annual Penghu International Fireworks Festival, though this draws large crowds.

Kinmen provides a fascinating window into the Cold War era, with military tunnels, bunkers, and museums documenting the tense decades of standoff with the mainland. Traditional Fujian-style architecture survives here better than on the main island, as development was restricted for security reasons.

Orchid Island offers the most authentic indigenous cultural experience in Taiwan, though visitors should approach respectfully and understand that tourism here is contentious. The island’s dramatic volcanic landscapes and exceptional diving attract those willing to make the journey.

Who Should Prioritise This Region

The offshore islands suit travellers with specific interests: beach lovers and divers (Penghu, Green Island); history enthusiasts interested in cross-strait relations (Kinmen, Matsu); those seeking remote island experiences (Orchid Island); and anyone wanting to add unique stamps to their Taiwan experience.

These destinations work best for travellers with flexible schedules, as weather can disrupt ferry services and flights. They’re not ideal for those on tight timelines or who need consistent urban amenities.

Climate Considerations

Penghu experiences strong winds, particularly in winter when the northeast monsoon makes the islands feel much colder than thermometer readings suggest. Summer (May to September) is the primary tourist season, with warm weather and calm seas, though typhoons can still disrupt travel.

Kinmen and Matsu have climates similar to southern mainland China: hot, humid summers and surprisingly cold, damp winters with occasional frost.

Green Island and Orchid Island share eastern Taiwan’s typhoon vulnerability and wet winters. The best weather for both comes in spring and early summer (April to June) before typhoon season intensifies.

For all offshore islands, always build flexibility into your schedule to account for weather-related transportation disruptions.

High Mountain

What It Encompasses

The High Mountain region isn’t a geographic area in the traditional sense but rather represents Taiwan’s alpine environments above approximately 2,500-3,000 metres. The Central Mountain Range contains over 200 peaks exceeding 3,000 metres, with Yushan (Jade Mountain) topping out at 3,952 metres: the highest peak in Northeast Asia outside the Himalayas and Tibet.

Distinctive Characteristics

Taiwan’s high mountains represent an entirely different ecosystem and set of experiences. Above 3,000 metres, the landscape shifts to alpine forests of hemlock and fir, eventually giving way to alpine meadows and bare rock near the highest peaks. Temperatures can drop below freezing even in summer, and snow blankets the highest peaks from December through March.

These mountains are ecologically precious, containing ancient forests and endemic species found nowhere else. They’re also culturally significant to Taiwan’s indigenous peoples, many of whom originated in these highlands and maintained mountain villages until relatively recently.

Access to Taiwan’s high mountains is strictly controlled. Popular peaks like Yushan require permits obtained through an online lottery system months in advance. Some areas require hiring licensed guides. This isn’t just bureaucracy: the mountains present genuine hazards including rapid weather changes, altitude sickness, and difficult terrain.

Key Highlights

For serious hikers and mountaineers, Taiwan’s high mountains offer experiences comparable to much more famous ranges but within a compact area. You can summit multiple 3,000-metre peaks in a single multi-day trek, traverse ancient forests, and camp at high-altitude refuges with spectacular views.

Several high-altitude roads provide access to alpine scenery without serious hiking. The Central Cross-Island Highway (partially closed but accessible sections remain), the Southern Cross-Island Highway, and roads to Hehuanshan allow you to reach above 3,000 metres by vehicle or bus, experiencing the vegetation zones change as you climb.

The mountains also offer some of Taiwan’s best birdwatching, with numerous endemic species including the Mikado pheasant, Swinhoe’s pheasant, and Taiwan blue magpie inhabiting different elevation zones.

Who Should Prioritise This Region

The high mountains appeal to experienced hikers and mountaineers seeking challenging, rewarding treks in spectacular alpine environments. They’re ideal for those who appreciate that Taiwan offers far more than night markets and tea culture: that it’s a genuinely mountainous island with peaks that would be considered serious mountains anywhere in the world.

However, this region demands proper preparation. You need appropriate equipment, reasonable fitness levels, and understanding of mountain hazards. The permit system requires advance planning that doesn’t suit spontaneous travellers.

Those who want to experience high-altitude environments without serious trekking can still enjoy driving routes and shorter walks in places like Hehuanshan, though even these require warmer clothing than you’ll need anywhere else in Taiwan.

Climate Considerations

Taiwan’s high mountains create their own weather, often dramatically different from the lowlands. Temperatures decrease approximately 6°C for every 1,000 metres of elevation gain. At 3,000 metres, even summer nights can drop to near freezing, whilst winter brings snow and ice from December through March, with the possibility of snow even in autumn and spring.

Weather can change rapidly, with clear mornings giving way to afternoon mist and rain within hours. The mountains generate their own cloud systems, and visibility can drop to metres in heavy fog.

The monsoon patterns affect the mountains differently than the lowlands. The northeast monsoon brings moisture to the northern ranges, whilst southern peaks receive more rain from summer monsoons. Typhoons can bring particularly dangerous conditions, with extreme rainfall triggering landslides and making trails impassable.

The most stable weather generally comes in autumn (October to November) and spring (April to May), though no season guarantees clear skies.

Cultural Differences by Region

Understanding Taiwan’s regional variations goes beyond geography and climate. The island’s regions have developed distinct cultural characteristics shaped by settlement patterns, economic development, political history, and the complex interplay between indigenous peoples, Han Chinese settlers, and more recent arrivals.

Historical Settlement Patterns

Taiwan’s cultural geography reflects waves of migration and settlement that occurred at different times and rates across the island. Indigenous peoples inhabited Taiwan for thousands of years before Dutch and Spanish short colonisation and significant Han Chinese settlement began in the 17th century. The early Chinese settlers, primarily from Fujian and Guangdong provinces, established themselves first in the southwest, particularly around present-day Tainan, before gradually moving northward and into the central plains.

The north, particularly Taipei, developed later and differently. When the Qing Dynasty took control of Taiwan in 1683, they initially restricted settlement and development, viewing the island as a frontier backwater. Only after Taiwan’s designation as a province in 1885 and then the Japanese colonial period (1895-1945) did the north develop rapidly. Taipei became the colonial capital, attracting bureaucrats, merchants, and workers from across the empire.

This historical pattern means that southern Taiwan, particularly Tainan, has deeper roots in traditional Taiwanese culture. Families trace their lineages back centuries, temples document hundreds of years of continuous worship, and traditional arts and crafts maintain stronger continuity. The north, by contrast, has always been more transient, more influenced by external power centres, and more oriented toward modernisation.

Language and Dialect

Regional identity in Taiwan is strongly tied to language. While Mandarin serves as the official language and lingua franca, Taiwanese Hokkien (often simply called Taiwanese) and Hakka remains the primary language for many, particularly older residents. However, the usage and status of these two languages varies significantly by region.

In the south, particularly Tainan and Kaohsiung, Taiwanese remains robust across generations. You’ll hear it spoken in markets, shops, temples, and homes. Local politicians often campaign primarily in Taiwanese, and speaking it signals genuine local connection. Even younger people in the south are more likely to be fluent in Taiwanese than their northern counterparts.

Northern Taiwan, particularly Taipei, has seen more dramatic language shift toward Mandarin. The concentration of mainlanders who arrived after 1945, the presence of government and educational institutions that enforced Mandarin, and the cosmopolitan nature of the capital have all contributed to Mandarin’s dominance. Many young people in Taipei understand Hokkien but speak it poorly or not at all.

Eastern Taiwan and the mountains have different linguistic landscapes altogether, with indigenous languages still spoken in many communities, though endangered. Each indigenous group has its own language, and these bear no relationship to Chinese languages, instead belonging to Austronesian language families.

The Hakka people, a Han Chinese subgroup, concentrated in certain areas—particularly parts of Hsinchu, Miaoli, and southern Taiwan—maintain their own distinct language and cultural practices.

For travellers, this means that English speakers will generally find easier communication in Taipei and other northern urban areas, where younger people have had more English education and international exposure. In the south and rural areas, fewer people speak English, but the cultural experiences are often richer for those willing to navigate the language barrier.

Religious Practices and Temple Culture

Taiwan’s religious landscape, a complex blend of Buddhism, Taoism, folk religion, and indigenous beliefs, manifests differently across regions. The south has higher temple density and more elaborate festivals, and religious practices more deeply woven into daily life.

Tainan contains the highest concentration of temples in Taiwan, many dating back centuries. Religious festivals here are major community events, with entire neighbourhoods mobilising for temple processions, opera performances, and ritual activities. The annual pilgrimage of the Dajia Mazu statue, which passes through central and southern Taiwan, represents one of the world’s largest religious processions, drawing millions of participants.

Northern urban areas have temples too, but religious practice is generally less intensive. Temples in Taipei often function more as tourist sites and occasional worship venues than as centres of intense community religious life. This reflects not just secularisation but also the more transient nature of northern communities, where people lack the generations-deep connections to local temples that characterise the south.

Eastern Taiwan and indigenous areas have their own religious patterns, with traditional indigenous beliefs often syncretised with Christianity, which spread through missionary activity during the Japanese period and after. These communities celebrate different festivals tied to agricultural cycles and ancestral traditions.

Political Culture

Taiwan’s regional political differences are substantial and well-documented. In general terms, southern Taiwan leans toward the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which emphasises Taiwanese identity and seeks to maintain distance from China. Northern Taiwan, particularly areas settled by mainlanders after 1945, has traditionally leaned toward the Kuomintang (KMT), which historically promoted closer ties with China and Chinese cultural identity.

These patterns reflect historical experiences. Southern Taiwan, with deeper roots in the island and greater distance from Chinese identity, more readily embraced the Taiwanese independence movement. The north, with more mainlanders and those whose families arrived in 1949, maintained stronger emotional and cultural ties to a broader Chinese identity.

However, these divisions are far more complex than a simple north-south split. Generational differences matter enormously: younger Taiwanese across regions increasingly identify as Taiwanese rather than Chinese, regardless of family origin. Urban-rural divides, economic interests, and local issues all complicate simple regional stereotypes.

For travellers, Taiwan’s political divisions rarely affect daily experience. Taiwanese people are generally welcoming regardless of visitors’ nationality or politics. However, being aware of regional sensitivities, particularly around issues of Taiwanese versus Chinese identity, helps you navigate conversations more thoughtfully.

Food Culture and Regional Cuisines

Regional food differences provide some of the most accessible and enjoyable ways to experience Taiwan’s cultural diversity. Each region has developed distinct cuisines based on local ingredients, historical influences, and cultural preferences.

Southern food, particularly Tainan cuisine, represents the heart of traditional Taiwanese cooking. The food here is generally sweeter than elsewhere: sugar appears in savoury dishes in ways that surprise even other Taiwanese people. This sweetness reflects southern Taiwan’s history of sugar production during the Japanese period. Tainan is particularly famous for its breakfast culture, with vendors and restaurants opening as early as 4 or 5 AM serving traditional dishes like beef soup, fish congee, and savoury rice dumplings.

Northern food, particularly in Taipei, is more diverse and international, reflecting the capital’s role as a crossroads. You’ll find every regional Chinese cuisine, international restaurants, and fusion experiments. The night market foods that tourists often associate with Taiwan like stinky tofu, oyster omelettes, pearl milk tea are available everywhere, but northern versions often differ in seasoning and preparation from southern ones.

Hakka cuisine appears in areas with Hakka populations, characterised by preserved and pickled ingredients that reflect the community’s historical poverty and agricultural lifestyle. Indigenous cuisines, found primarily in the east and mountains, feature wild greens, game meats, and preparations that differ entirely from Chinese cooking traditions.

Central Taiwan has developed its own food culture, with Taichung claiming several iconic inventions including bubble tea, sun cakes, and particular noodle preparations. Eastern Taiwan’s indigenous influence brings foods like bamboo tube rice (sticky rice steamed in bamboo) and wild mountain vegetables.

For food-focused travellers, this regional diversity means that spending time in multiple regions provides genuinely different culinary experiences, not just variations on the same dishes.

Pace of Life and Social Customs

Perhaps the most immediately noticeable regional difference is pace of life. Taipei moves fast: people walk quickly, rush between metro stations, and maintain schedules. The city runs on efficiency, punctuality, and productivity. Social interactions in Taipei can feel more reserved, less spontaneous, more bounded by modern urban etiquette.

Southern cities like Tainan move noticeably slower. People linger over meals, chat with shopkeepers, and maintain older patterns of social interaction where personal relationships matter more than efficiency. Shops might close for long lunch breaks, business happens at a more relaxed pace, and strangers are more likely to strike up conversations.

Eastern Taiwan and rural areas everywhere move slower still. Agricultural rhythms still structure daily life in many places, with work patterns following season and daylight rather than clock time. Social customs here often retain more traditional elements—offering tea to visitors, maintaining more formal greeting customs, and stronger expectations of community reciprocity.

For travellers, these differences mean adjusting expectations. In Taipei, you can plan tight schedules and expect things to run on time. In the south and east, building in flexibility and accepting a slower pace will make your experience more pleasant and authentic.

Connecting the Regions

Understanding Taiwan’s regions is valuable, but most travellers will want to visit multiple regions during their trip. Taiwan’s compact size and excellent transportation infrastructure make this eminently feasible, but the specifics of how to connect regions significantly affect your travel experience.

The East-West Divide

The Central Mountain Range creates Taiwan’s most significant travel barrier. No direct roads or railways cross the mountains at their highest points, so moving between east and west requires either going around the island or taking one of several mountain roads that cross at lower elevations.

The most dramatic connection is the Suhua Highway, hugging the cliffs between Hualien and the northeast coast, offering spectacular views but prone to closure from landslides and typhoon damage. The Central Cross-Island Highway, once the main route between Taichung and the east, suffered severe typhoon damage in 2004 and remains largely closed, though sections at either end remain accessible.

The Southern Cross-Island Highway provides another route, though it’s long and winding, better suited to leisurely exploration than efficient transit. Most travellers moving between east and west rely on either the northern route via the Suhua Highway or simply take the train around the north or south of the island—a longer but more reliable journey.

This geographic reality means that visiting eastern Taiwan requires deliberate planning. It’s not a place you casually add to a Taipei-based itinerary; it deserves dedicated time. However, the journey itself, whether by car along the coast or by train, becomes part of the experience, revealing Taiwan’s dramatic topography.

The Railway Network

Taiwan’s railway system provides the backbone for inter-regional travel. The Western Main Line runs from Keelung through Taipei, Taichung, Tainan, and Kaohsiung, connecting all major western cities with frequent service. The High Speed Rail (HSR) parallels this route, reducing travel time dramatically: Taipei to Kaohsiung takes less than two hours on the HSR versus four to five hours on conventional trains.

The Eastern Main Line runs from Keelung through Yilan and down the east coast through Hualien to Taitung, eventually connecting back to the south. This line is slower and less frequent but offers spectacular coastal views.

For travellers, this means that visiting multiple regions by public transportation is entirely feasible. A sample itinerary might include Taipei (north), Taichung or Sun Moon Lake (central), Tainan (south), and Hualien or Taitung (east), all connected by rail. The HSR makes even day trips feasible—you could breakfast in Taipei and lunch in Tainan, though this would be rushed.

However, the railway network has limitations. The railway connects major cities efficiently, but rural areas, mountain destinations, hot springs, indigenous villages, smaller beaches, and most hiking trailheads require buses that may run infrequently or not at all. In eastern Taiwan particularly, not having your own vehicle means you’ll miss many of the region’s most appealing aspects.

Many experienced Taiwan travellers adopt a hybrid approach: use public transportation for city-to-city travel, then rent vehicles (cars or scooters) for specific regions where they’re most valuable. You might take the HSR to Hualien, rent a car there for exploring the east, return it before taking the train to Tainan, and explore the south by public transport and occasional taxis.

Seasonal Considerations for Multi-Region Travel

Taiwan’s regional climate variations mean that the ideal season for visiting multiple regions requires compromise. No season is perfect everywhere, but understanding regional patterns helps you make informed choices.

Winter (December to February) favours the south, with mild, pleasant weather in Tainan, Kaohsiung, and Kenting, whilst the north remains grey and damp and the east faces northeast monsoon rain. A winter itinerary might emphasise southern Taiwan with perhaps a stop in Taipei, accepting that you’ll need rain gear in the capital.

Spring (March to May) offers the most balanced conditions, with warming temperatures everywhere and less rain than winter in the north and east. However, spring weather can be unpredictable, with warm days followed by sudden cold fronts, and the plum rain season in May brings extended wet periods. Spring is excellent for visiting multiple regions, particularly combining the north with the east or mountains.

Summer (June to August) brings hot, humid weather everywhere, with Taipei and the lowlands often exceeding 35°C with oppressive humidity. However, summer is the best season for beaches (Penghu, Kenting), and high mountain areas become gloriously comfortable. A summer itinerary might combine Taipei (accepting the heat), the mountains (escaping it), and eastern or southern beaches. The major constraint is typhoons, which peak in July and August and can disrupt plans significantly.

Autumn (September to November) rivals spring for overall conditions, with warm but less oppressive temperatures, generally stable weather (though September still sees typhoons), and excellent visibility for mountain views. Autumn is perhaps the single best season for visiting multiple regions, particularly for outdoor activities and photography.

For multi-region itineraries, moving from north to south generally means moving toward better weather in winter, whilst moving south to north does the same in summer (though you’re trading heat for heat, just slightly less of it). Moving east to west or vice versa doesn’t significantly change climate patterns, though the east generally receives more rain.

Conclusion: Choosing Your Taiwan

Taiwan’s regional diversity means that no single trip can capture everything the island offers, nor should it try. The travellers who gain the most from Taiwan are those who accept this limitation, choose regions that align with their interests and the season they’re visiting, and explore those areas with enough depth to move beyond surface impressions.

Your Taiwan might centre on food culture in Tainan, hiking in the mountains, indigenous encounters in the east, or urban sophistication in Taipei. It might involve slow travel in a single region or efficient sampling of several. It might prioritise nature over culture, history over modernity, or seek some balance of all these elements.

The framework this guide provides, understanding what each region offers, who it suits, and how regions connect, helps you make these choices deliberately rather than defaulting to a generic itinerary that tries to include everything and satisfies nothing fully.

Taiwan’s small size is simultaneously its limitation and its advantage. You cannot see everything in one trip, but you can genuinely understand a region or two rather than merely passing through. You can have in-depth experiences like hiking a serious mountain, learning about temple festivals, discovering what makes Tainan’s food culture distinctive, rather than collecting superficial impressions of many places.

As you plan your journey through Taiwan’s regions, remember that this guide provides frameworks for decision-making, not prescriptions. The “best” region depends entirely on your interests, the season, your tolerance for language barriers, your outdoor skills, and what you hope to gain from travel. Some travellers never leave Taipei and have rich experiences; others skip the capital entirely and focus on rural Taiwan or the mountains.

What matters is making conscious choices based on understanding what different regions offer, then exploring those places with sufficient time and openness to appreciate their distinct characters. Taiwan rewards this approach with experiences that move beyond the generic Asia trip, revealing an island that’s simultaneously Chinese and indigenous, traditional and modern, densely populated and surprisingly wild.

The regions of Taiwan aren’t just geographic divisions: they’re windows into different aspects of what makes this island distinctive. By understanding them, you position yourself not just to visit Taiwan, but to begin understanding it.

-

Actually it’s more common to divide Taiwan into five regions: North, Central, South, East, Kinmen-Matsu, which Offshore Islands and High Mountain regions are merged into other regions. But here we use six regions since it’s easier to introduce the difference between them. ↩︎